Guest Blog by Phil Hedrick

Conservation of the Mexican wolf, a unique subspecies of gray wolf, has been a qualified success, with real progress made in the United States and a number of threats looming throughout the species’ range but especially in Mexico.

Wild populations of Mexican wolves (Canis lupus baileyi) were historically distributed in northern Mexico and the southwestern U.S. At one point, it’s estimated that there were 1,500 wolves in New Mexico alone. From habitat analysis, it’s reasonable to assume that a similar number were in Arizona, putting the pre-European numbers in the U.S. around 3,000 individuals and even higher in Mexico.

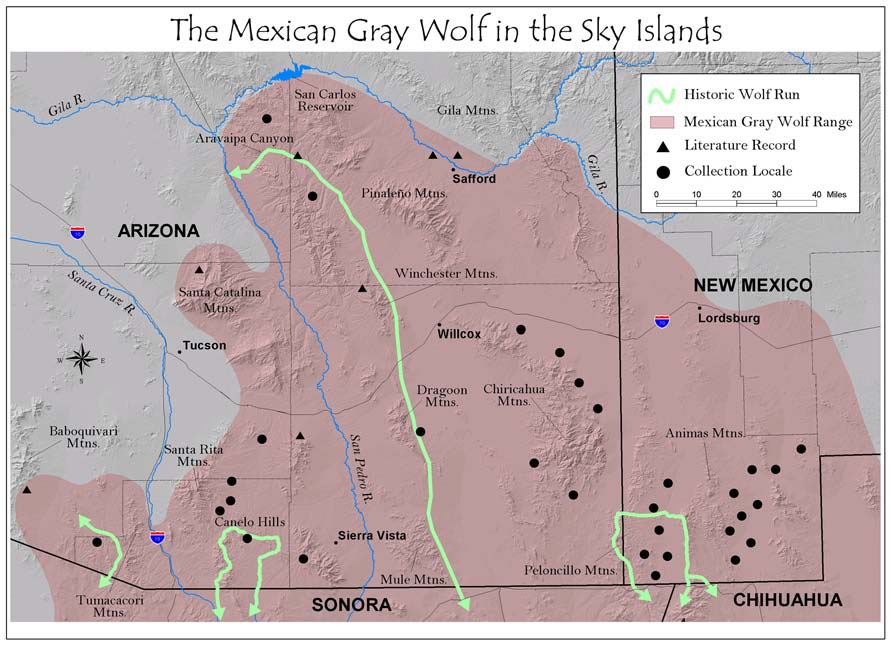

Below is a map showing some of the historic “wolf runs” in the Sky Islands, info obtained mainly from wolf trappers during the wolf-eradication era. Ordinarily, wolves would have defended local territories and not traveled regular long-distance circuits.

By the 1970s, however, organized killing of Mexican wolves at the behest of influential cattle ranchers resulted in government-sponsored eradication programs that eliminated these wolves from the U.S. and nearly eliminated them in Mexico.

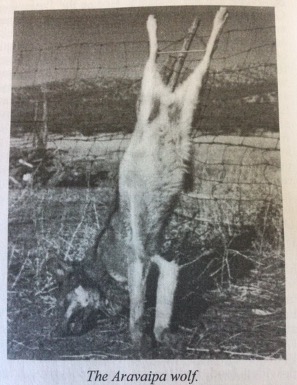

No epitaph of the wolf in the Southwest could be written without mentioning the Aravaipa wolf in Arizona. This wolf was taken by a private trapper in 1976 for a reputed bounty of $500, put up by local stockmen. It was likely the last wild Mexican wolf killed in the United States.

Given the consequent endangered status of Mexican wolves, a captive-breeding program was developed. And Roy McBride, a trapper from Texas who had long killed Mexican wolves, was hired to capture new individuals to now save the species. He caught six wolves in Mexico between 1977 and 1980, one of whom died in the trap. Three of the remaining five became the founders of what’s come to be known as the “McBride lineage” of Mexican wolves.

All Mexican wolves today — around 260 individuals in the wild and around 380 individuals in captivity — descend from the seven founders from three captive lineages that made very unequal contributions to the present-day population. Specifically, the three founders from the McBride lineage contributed about 77% of the genetic ancestry. The two founders from the captive Ghost Ranch lineage held in New Mexico contributed only about 16%. And the two founders from the Aragon lineage from Mexico contributed only about 7%. As a result, the estimated genetic foundation of the wild population of Mexican wolves is one of the smallest and most limited of any reintroduced endangered species — a fact that, if ignored, portends severe genetic problems such as physical deformities, reduced disease resistance, and lower reproductive potential, and could ultimately lead to population decline and extinction.

In 1998, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists released descendants from these founders in the Blue Range area near the Arizona-New Mexico border. The aim was to restore a viable wild population as an essential next step toward recovering Mexican wolves.

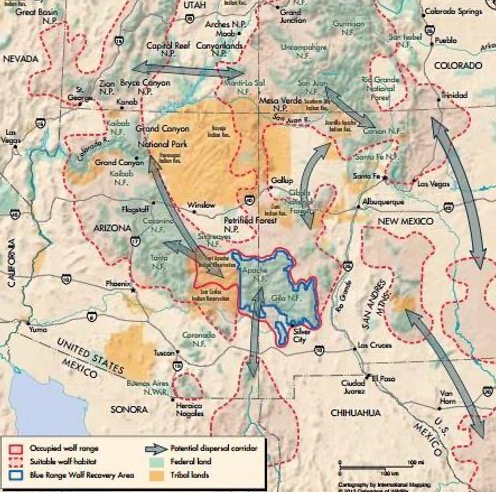

The larger strategy was to establish three connected populations — including the present one along the Arizona-New Mexico border, one in the Grand Canyon ecoregion, and another in the southern Rockies — that together would provide a more resilient “metapopulation” for Mexican wolves similar to the ones that have been successful for other wolves. In fact, the Kendrick Peak pack has recently naturally dispersed and established northwest of Flagstaff, Arizona, in the Grand Canyon area. But whether the wolves will be allowed to stay in the region is still unknown.

The science behind this overarching plan came from the 2004 and 2011 Mexican wolf recovery teams, composed almost entirely of scientists with either wolf biology or conservation biology expertise (17 of 18 members). Together, they concluded that Mexican wolf recovery would require three connected populations (a metapopulation) in the United States, each with a census number of at least 250 wolves. These criteria were based on establishing a metapopulation large enough to avoid short-term inbreeding depression and to avoid extinction in the near future.

Similar recommendations calling for three connected populations were previously made for both the recovery of gray wolves in the northern Rockies (in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming), as well as Great Lakes wolves (in Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin). At this point, there are about 2,800 wolves in the three northern Rockies states, plus about 450 in the neighboring states of Washington, Oregon, California, and Colorado. And there are about 4,300 wolves in the Great Lakes states — in other words, many more in both areas than the 750 wolves recommended by the Mexican wolf experts in 2004 and 2011.

Having three connected populations for Mexican wolves is crucial because it would provide a safety net if one or two populations experienced a large disease outbreak or other catastrophe, or if there was extensive human killing of wolves as has occurred in the present reintroduced population. Because genetic variation for future adaptation is fundamental given many environmental challenges, a large metapopulation size is highly recommended.

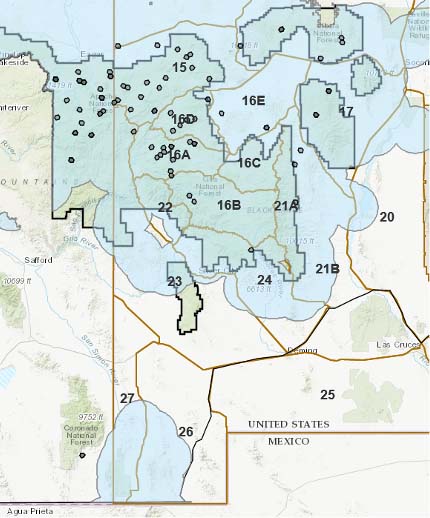

In 2022, a pack that initially consisted of the female wolf known as Llave (1828) and a male lobo (1582) was released. But the following year Llave’s mate was killed. She moved around a great deal, as you can see in the map below, and was then recaptured and paired in captivity with a male lobo known as Wonder (2774). This pair was released in 2024 and has since established a territory in the Chiricahua and Peloncillo mountains along the Arizona-New Mexico border.

As for the population in Mexico, recent reports have been grim and it’s unlikely to contribute to metapopulation recovery because border-related infrastructure is already impeding wolf movement along much of the U.S.-Mexico border. Also, there’s a limited natural prey base in Mexico with few deer and no elk. Although more than 70 wolves have been released in Sonora and Chihuahua, there are no collared wolves remaining there, despite an effort to supplementally feed them large amounts of pig carcasses. The median life span after release for collared wolves in Mexico has been extremely low at just 2.5 months. As a result, releases in Mexico have now been halted, and the few uncollared wolves potentially remaining in the country are likely inbred and on private land with abundant livestock nearby and widespread risk of being killed.

It’s a challenging situation. But even so, there are real steps that can be taken to significantly advance lobo recovery. As noted earlier, establishing three connected populations will be key, as will allowing some breeding with northern gray wolves (another subspecies) to enhance the genetic vigor of Mexican wolves. With northern gray wolves already established in western Colorado, and Mexican wolves like the Kendrick Peak pack pushing north toward the Grand Canyon, the distance between the two isn’t far. Decision-makers could also help by removing the current barrier to Mexican wolf dispersal north of I-40 and by facilitating transnational movement between the U.S. and Mexico by leaving passages in the border wall along the most likely dispersal corridors. And lastly, state and federal biologists, who have a legal mandate under the Endangered Species Act to make decisions based solely on the best available science, should not impede these movements and should let nature take its course.

Phil Hedrick is a conservation biologist and population geneticist, now retired from Arizona State University. He is the author of many articles on endangered species, including ones on wolves, topminnows, and salmon. He can be reached at philip.hedrick@asu.edu.