Guest blog by Axhel Muñoz

Great charismatic mammals like the jaguar and ocelot grace the Sky Island mountains of Sonora and Arizona, but there are other endearing creatures that inhabit this landscape.

The lesser long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae) is one such creature. They live in Mexico and the southwestern U.S., where unlike most bats, which feed on insects, they feed on nectar but also consume pollen and fruits. These medium-sized bats have a long narrow snout that ends in a small triangular “nose-leaf.” Their tongues are rough with long ridges — great for lapping nectar. And their wings are built for long-distance flight in open habitats but not so great for chasing insects.

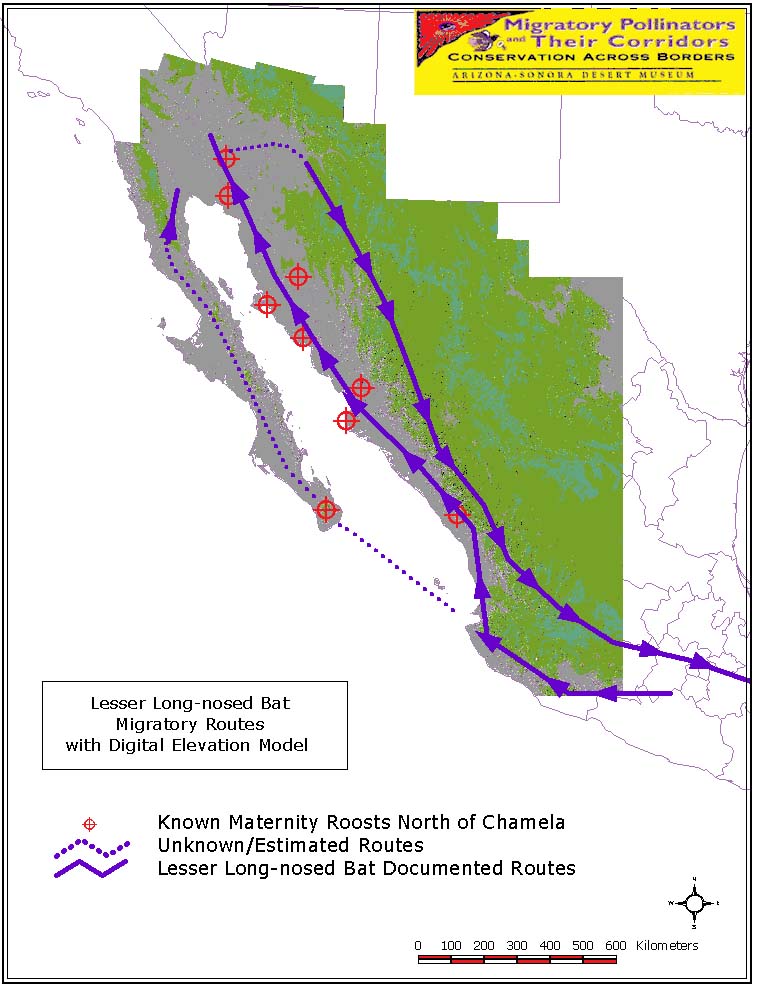

Lesser long-nosed bats are migratory. When traveling in the northern part of their range, they follow a nectar corridor of columnar cacti in the lowlands and agaves in the highlands.

In the late spring, summer, and early fall, they spend their time in Arizona and Sonora looking for food and rearing their babies. Then in the winter many fly south toward the state of Jalisco in Mexico, continuing their good work as pollinators and helping make possible tequilas and mescals.

The nocturnal pollination of columnar cacti by lesser long-nosed bats has important cultural implications, since many native peoples of the Southwest and Sonora use their fruits as part of their cuisine and ceremonies. Whether it’s the Tohono O’odham using saguaro fruits in Arizona or the Comcaac, also known as the Seri, collecting cardon and organ pipe fruits in Sonora, the availability of these food sources when other plants aren’t producing is a blessing. Although the relationship between people and columnar cacti is an amazing story unto itself, it’s the story of the lesser long-nosed bats, agaves, and Sky Islands that I’d like to further explore.

A Who’s Who of Agave Pollinators in Our Region

Lesser long-nosed bats are nocturnal pollinators of agaves. But they’re not the only ones and, in fact, many other animals in the Sky Islands can do the job. Although nectar production in Palmer’s agave (Agave palmeri) happens mostly between 6 p.m. and midnight, there’s still plenty of nectar available in the morning, as well as pollen. A great variety of insects such as sweat bees, carpenter bees, hawk moths, wasps, and flies take advantage of Palmer’s agave flowers as a resource. That said, insects aren’t the most efficient agave pollinators. In one study, insects were observed to contact the stigma (female part of the flower) and transfer pollen (male part of the flower) just 1% of the time. The reason this works out for the plant is that there are so many insects visiting it that effective pollination still takes place.

In the study, rufous and black-chinned hummingbirds, as well as Scott’s and Bullock’s orioles, also visited Palmer’s agave flowers. Hummingbirds were frequent, but did not contact the stigma in the flowers, so they weren’t considered pollinators. The orioles did pollinate the plants, but were rare.

Lesser long-nosed bats, on the other hand, consistently pollinated the plants. Thus, alongside insects as a group, these bats are essential for the reproductive success of Palmer’s agave. And together they account for most of the seed production of these iconic plants that shoot up their magnificent stalks and grace our Sky Island hillsides.

Why This Matters for the Years Ahead

Palmer’s agaves are found at elevations between 3,000-6,450’ in the Sky Islands of Arizona and Sonora (as well as western parts of New Mexico and Chihuahua). They can tolerate temperatures ranging from

As a result, Palmer’s agaves are essentially stuck in various corners of the Sky Islands and would be completely isolated from each other genetically if not for the animals that help them connect across mountain ranges and build further resilience in times of change.

On this front, insects have a limited ability to help. They may exist as a species across many mountain ranges, but each individual insect can only fly so far after it has pollinated an agave. Lesser long-nosed bats, however, can cover great distances, and this is where they become indispensable. They help the agaves stay genetically connected from one mountain range to another. And their adaptations for feeding on nectar and long-range flight make them the perfect pollen “taxi rides.”

With our current changes in climate and expected increases in temperatures and aridity, the need for genetic diversity in agaves (and so many other species) only increases. This is what will afford them the flexibility to adapt. It’s a wonder how it’s all made possible, thanks to this ecological dance between agaves and lesser long-nosed bats.

Axhel Muñoz is a naturalist and dynamic environmental educator from the Sonoran Desert region and a Sky Island Alliance board member. Over the years, he’s worked on numerous conservation projects in Puerto Rico, Costa Rica, Brazil, California, and Arizona. And he’s taught teacher workshops, as well as students from kindergarten to university.

References

England, Angela E. 2012. “Pollination ecology of Agave palmeri in New Mexico, and landscape use of Leptonycteris nivalis in relation to Agaves.” Dissertation, University of New Mexico. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/31

Howell, D.J. and Hodgkin, N. 1976. Feeding adaptations in the hairs and tongues of nectar-feeding bats. Journal of Morphology 148(3): 329-39.

Sahley, C.T. et al. 1993. Foraging behaviour and energetics of a nectar-feeding bat, Leptonycteris curasoae (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Journal of Zoology 244(4): 575-586.

Slauson, Liz A. 2000. Pollination biology of two chiropterophilous agaves in Arizona. American Journal of Botany 87(6): 825-36.