With border wall actively under construction in Southern Arizona, it’s a race against time to document the wildlife community living in unwalled stretches of the international border today. We designed a study to thoroughly document which wildlife species are migrating through and residing permanently in the border zone transecting the Patagonia and Huachuca Mountain foothills. The study is underway now to define the wildlife community. We will monitor for change over time, if and when, the border wall cuts through this landscape. Our data will evaluate the wall’s environmental impact and guide the future protection and restoration of vital wildlife pathways. Our project is especially crucial today because the Trump’s administration has waived environmental laws that require any study prior to construction.

The Camera Array

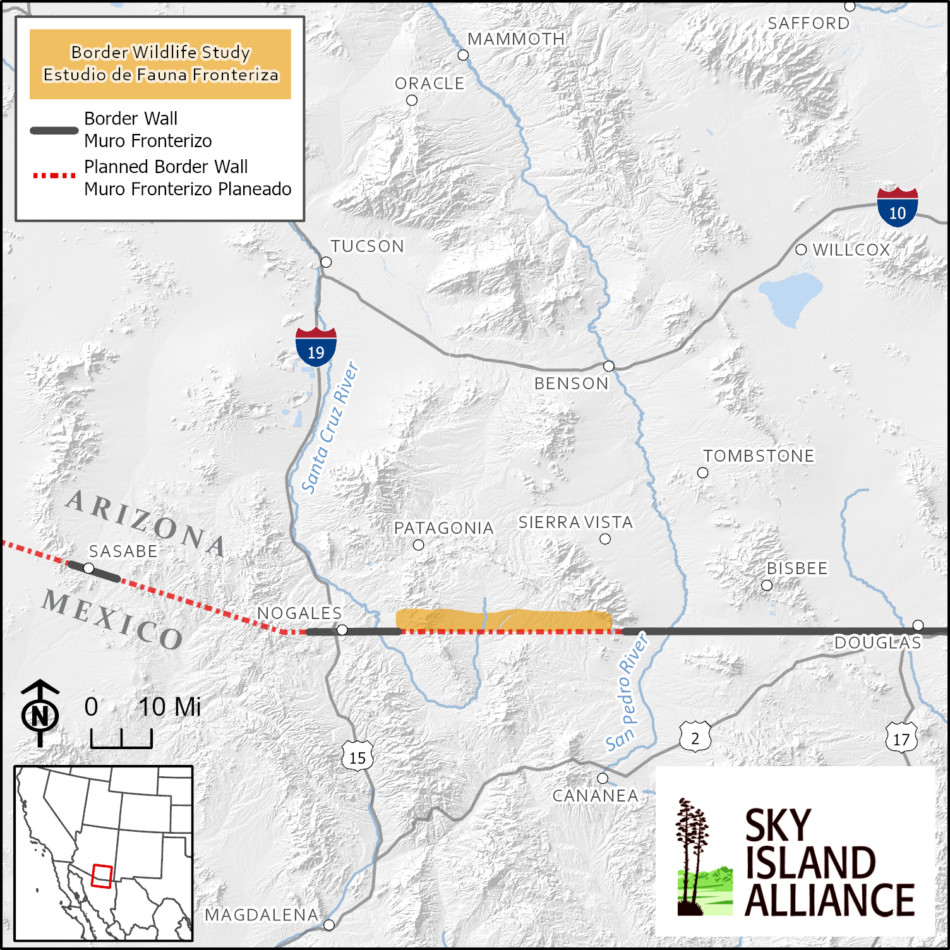

The Border Wildlife Study transverses the Patagonia and Huachuca Mountains in Southern Arizona, an area of border only marked with barbed wire and vehicle barrier today but where border wall construction is planned. Map created by Sky Island Alliance GIS Specialist, Sami Hammer, on March 2020.

Our camera array has more than 50 camera trap points arranged in a grid along 34 miles of the border. Every camera is within 3 km of the border and 2 km from the closest adjacent camera in the study. Each passive infrared camera triggers when it senses motion and heat to capture images of wildlife 24 hours a day and 7 days a week.

This design creates a network of camera points optimized to detect both wide-ranging large mammals like jaguar and small animals like coati and birds. Our design is based on the global wildlife monitoring standard—TEAM Terrestrial Vertebrate Protocol (2011)—and it is used by the National Park Service, Parks Canada, and numerous wildlife biologists in ecosystems across the planet.

Because the TEAM protocol selects regularly spaced camera locations across different landscape features and habitats, it removes bias in camera placement, increases the likelihood of documenting the true breadth of the wildlife community, and allows for direct scientific comparison between camera points because they are selected the same way.

Here’s an example to explain why this matters: It’s compelling to place a camera on a water source like a spring or stream because many animals come to drink there—but actually some prey animals avoid springs because they are frequently used by predators and therefore it is too risky for them to approach the water source and drink. By randomly placing cameras across a landscape using the TEAM protocol, some of our cameras were placed near water sources, but many were not—increasing the likelihood of observing a wide variety of species and truly measuring the diversity of wildlife in our region.

Counting Species Over Time

At every camera point and for the whole camera array collectively, we will keep track of each new species as it is detected. With these data, we will create a species accumulation curve—scientist speak for how many species are detected over time. These data will provide evidence of wildlife occupancy at the border zone and the shape of this curve will also alert us to when we have likely detected a majority of the species each study area. We detected 27 mammals and birds species in only the first week of the study, so the wildlife community here is proving to be diverse and active this spring.

If we can continue the study post-border wall construction, then we will compare the future wildlife community with the one we are measuring today to learn how the wall impacts the number of species able to thrive in the borderlands bisected by wall. It all starts with learning what species live in this special place now. Without knowing who is there, we cannot possibly begin to design the conservation strategies to protect them.

Visit the Border Wildlife Study project page for research updates and please consider sponsoring a camera to help make this important conservation science possible. Donate today.

Reference: TEAM Network. 2011. Terrestrial Vertebrate Protocol Implementation Manual, v. 3.1. Tropical Ecology, Assessment and Monitoring Network, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA.